I ended Part 1: Ontology and Epistemology of Post-Truth with “So what do we do about that?”

Not exactly a call to action, but perhaps a springboard for one.

What do we do once we frame “Post-Truth” as an epistemological stance of subjectivity? Does it make a difference in our actions–how we approach the “problem”, especially as academics and instructional designers?

I think it does. I think we must consider “Post-Truth” not just as an effect of low digital and media literacy but as an epistemological perspective in order to create a lasting and impactful change. Not that digital literacy isn’t important! Because I certainly think it is! But because our personal epistemology frames our literacies.

So what do we do now?

I’m going to approach this from a critical instructional design perspective.

The most important word in that sentence being critical. We must be critical. We must give power to learners and offer them opportunities to create knowledge–not a free-for-all–but knowledge supported by evidence through crafted arguments. We must make room for uncertainty, for both instructors and the instructees.

We must embrace education not as an interaction between an authoritative teacher and receptive students, but as an interaction among peers. Peers who are equally capable of bringing important insights to the table. Peers who support and challenge one another: in being critical, in seeking out multiple sources of evidence and shaping arguments; in having emotions and processing feelings; in being representatives of humanity.

We must have a pedagogy and praxis of love.

And we must focus on local truths, rather than one grand-narrative. Destroy the notion of objective versus biased, and accept that things are inherently and deeply connected to our experiences and interpretations of the world. Not everyone will interpret things in the same way. And that is OK. A multitude of voices and perspectives is valuable.

There are many ways to do this.

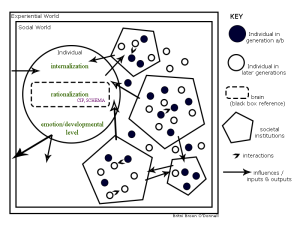

We start by evaluating out own epistemology, our own beliefs about knowledge, knowing, and reality. Reflecting on our practices and how our epistemology shapes them and imposes beliefs on others–especially when we serve as instructional designers and teachers–where we have power, and voice, and agency.

And we continue by giving that power, and voice, and agency to others. We create opportunities for questioning. And welcome uncertainty. We require evidence and well reasoned arguments, rather than “correct” choices. We focus on the local rather than the standardized.

We embrace the complexity and messiness of life. Of learning.

As an instructional designer, I challenge you to make your performance objectives (and thus assessments!) more open-ended. If you use Bloom’s taxonomy, aim higher–use verbs like: explain, describe, suggest, provide evidence for… Create instruction that gives your learners room to grow, to question, to challenge, to create their own knowledge, to define local truths.

And treat them as peers who have something valuable to offer. Because they do.